by Michael Baggot

View highlights of the event below:

View the afternoon session that began with the round table discussion:

How do your sacred texts view religious liberty? What convergences and divergences do you find between your religion and the text Dignitatis Humanae? What are the chief obstacles to interreligious dialogue? What would you say to those who use violence in the name of religion?

These provocative questions guided the December 10th round table discussion between Rabbi Riccardo Di Segni, Chief Rabbi of the Hebrew community in Rome; Dr. Maria Angela Falà, President of Interreligious Dialogue of the Maitreya Foundation; Imam Yahya Sergio Yale Pallavicini, Director of Interreligious Dialogue for the Mosques of Rome.

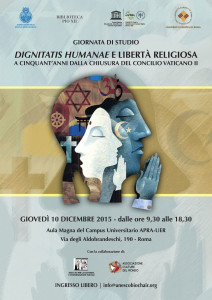

UNESCO Chair Director Alberto Garcia moderated the conversation as part of the day of study “Dignitatis Humanae and Religious Liberty” held at the Pontifical Athenaeum Regina Apostolorum and the European University of Rome to commemorate the 50th anniversary of the closing of the Second Vatican Council which promulgated one of the most influential documents of contemporary interreligious dialogue.

The Library Pius XII and the UNESCO Chair in Bioethics and Human Rights organized the day of study in collaboration with the Institute for Social Doctrine and Information and the Association of World Culture.

Alberto Garcia speaks to Telepace about the event. See minutes 1:20-1:45 and 10:15-12:45:

How do your sacred texts view religious liberty?

Falà noted that the scriptures of Buddhism did not contemplate religious liberty, as understood today. The contemporary notion of religious liberty was born in Europe. Traditionally, an ethics of duty and respect for the other has characterized Buddhism, instead of a vision focused on rights. However, Buddhism has long encouraged individuals to respond to other communities with respect, not violence. There are thus aspects of the Buddhist tradition, particularly the 10 social actions, which open the religion to embrace some of form of religious liberty.

Di Segni likewise noted that the scriptures of his Jewish tradition do not contemplate the modern notion of rights. In fact, certain passages of the Hebrew Bible seem to negate religious diversity. For instance, Deuteronomy chapter 7 contains exhortations to destroy the temples, statues, and other revered objects of neighboring religions. In general, the Hebrew Bible speaks more of duties than of rights. Many sections emphasize the chosen people’s call to acquire and maintain a territory in which laws should imposed. A possible connection between the Hebraic scriptural tradition and contemporary human rights comes in the concept of a Noahic covenant with seven fundamental principles to which all men are expected to observe.

Pallavicini first insisted that it is necessary to appreciate the context of Koranic revelation. He noted that it was addressed to a minority seeking truth and a pure worship. The message of Koran was sent to overcome an age of ignorance marked by the “sin of association,” that is to say, contact with idols. Various Arab tribes had occupied the land and sought to affirm their idolatry. In this tribal context, the Koran exhorts the renewal of the worship of pure monotheism exemplified in Abraham. Religious liberty is thus seen primarily in contrast with idolatry. Second, Pallavicini spoke on the history of prophecy in which many, but not all, of the various spokesman of God are mentioned. The Koran shows special reverence towards Muslims, Jews, and Christians as “People of the Book.” Moreover, it respects the wise men not explicitly mentioned, such as great Buddhists, Hindus, and Taoists. Third, Pallavicini highlighted the current period of decadence in Islamic culture. There are a scarcity of authentic teachers, while there are many formalists obsessed with politically ideological interpretations of the Koran. Finally, we must honestly confront the Koranic texts that harshly criticize other religions.

What convergences and divergences do you find between your religion and the text Dignitatis Humanae?

Di Segni noted that he and other Jews still find the conciliar document’s affirmation of Christianity as the one and true religion an obvious point of contention in their dialogue. However, his religious community generally agrees with the same document when it adopts human rights language akin to that found in international constitutions.

Falà shared that for Buddhism, the major point of contention is the problem of truth. When speaking of truth, a Buddhist will be inclined to ask “Which truth?” Falà clarified that in Buddhism, Truth (with a capital “T”) does not exist. The tradition can thus speak of orthopraxis, but not orthodoxy.

Pallavicini similarly chided Dignitatis Humanae for its exclusivism, that is, the Catholic Church’s refusal to allow for the possibility of other ways to absolute truth. This vision produces the danger of viewing one supreme religion over and above other secondary religions. Nonetheless, the Islamic community would be generally favorable to the Catholic document’s warning against aggressive secularism.

What are the chief obstacles to interreligious dialogue?

Falà recalled that interreligious dialogue is created by doing it. However, this dialogue should not be reserved to formal gatherings, but should rather enter the marketplace and daily life. Formal encounters are not enough, since they can leave without authentic appreciation for the other.

Pallavicini explained that ignorance, fundamentalism, and violence constantly threaten interreligious dialogue. We need individuals who have studied and lived their religion to combat ignorance. There is the danger of viewing oneself as the ruler of truth. His experience has shown Pallavicini that interreligious dialogue can aid intrareligious dialogue that seeks to purify a particular tradition of the three threats previously alluded to.

Di Segni urged the audience to keep in mind the goal of interreligious dialogue. He encouraged the path of mutual understanding and warned against the path of conquest of the other.

What would you say to those who use violence in the name of religion?

Di Segni explained the feast of Hanukah as a celebration of religious liberty against Hellenism. He noted that in an event with a long military conflict, his religious tradition has not emphasized the battles, but rather a peaceful miracle of candles. He insisted that exaggerated fundamentalism profanes authentic religion.

Falà reminded the audience that religion should be essentially a search for truth, unity, and ethics. It should educate in fundamental values, not separate. While violent Muslims gain most attention in the western media, she admitted that practitioners of Buddhism are not exempt from the shamefully violent acts.

Pallavicini observed that God’s name manifests his presence. Terrorism committed in his name is therefore a form of blasphemy. The invocation of his name should contribute to peace and contemplation, not bloodshed. Muslims are actually the largest group of victims of Islamic terrorism, thus presenting a horrid fratricide to the world. Pallavicini also encouraged attentiveness to the pretexts of dialogue. Unfortunately, some use what they call dialogue to legitimize their pet ideologies. Some even hold dialogue with particular groups as a platform for wagging ideological war against outsiders.

The panelists expressed their sincere desire that their stimulating encounter mark the first of many meetings to form a culture of mutual understanding and constructive cooperation among members of different religions in a world too often tarnished by ideological violence.

Read the full program here.

View the morning session: