By Alberto Carrara (translated by Adrian Lawrence)

We find ourselves in Spain in the middle of a bull fight. The audience is applauding the undaunted bullfighter. In comes the famous beast which strikes fear in men’s hearts. It’s an enormous animal that would put any common mortal in a cold sweat. The show has begun, but something strange happens. At the sight of the red cape, the “brute” hesitates, then turns around and goes back indifferently to the door from whence it came. A brief silence ensues. The initial laughter of the crowd turns into cries of protest. What’s going on with the bull? Did it loose its head?

We find ourselves in Spain in the middle of a bull fight. The audience is applauding the undaunted bullfighter. In comes the famous beast which strikes fear in men’s hearts. It’s an enormous animal that would put any common mortal in a cold sweat. The show has begun, but something strange happens. At the sight of the red cape, the “brute” hesitates, then turns around and goes back indifferently to the door from whence it came. A brief silence ensues. The initial laughter of the crowd turns into cries of protest. What’s going on with the bull? Did it loose its head?

And exactly its head—or better yet, its brain—is the problem.

How is such a sudden change of behavior possible? The Spanish scientist José Delgado explains it with his experiments that earned attention from the New York Times on 17 May 1965. Delgado implanted an electrode in the brain of a bull. The stimulus generated and controlled by the investigator was able to stop the fearsome charge of the animal excited by the red color of the cape. In a second experiment, besides just stopping, the bull actually turned around and trotted off as if nothing had happened.

These results of Delgado, together with experiments using LSD (lysergic acid diethylamide) on elephants carried out in the ’60s by the American psychiatrist Louis West, marked the first serious attempt to evaluate, from an ethical viewpoint, the modern advances and discoveries in the field of the neurosciences.

Here was born, although still only implicitly, modern neuroethics.

An initial definition of neuroethics could already be glimpsed from the very purpose of the numerous studies the Hastings Center promoted in the ’70s, namely, examinations of the ethical problems relating to the surgical and pharmaceutical interventions preformed on the human brain. Nevertheless, even if the term appears (as the neuroethicist Judy Illes reports) in the scientific literature from as far back as 1989, its first definition is considered to be that of May 2002. On this date in San Francisco the first world congress of experts was held: “Neuroethics: Mapping the Field”. The merit goes to William Safire, a political scientist of the New York Times, for the contemporary definition: “neuroethics is that part of bioethics that is interested in establishing what is licit, that is, what can be done in respect to therapy and the improving of brain functions, as well as evaluating the diverse forms of interference and unsettling manipulations of the human brain.”

The ever faster application of neuroscientific discoveries to human beings, fruit of the abundant investigations that try to decipher the mysteries of the human brain and mind, have elicited feelings in the general public that are often opposed and hostile. Precisely because of the “human” character of these advances rises their corresponding ethical reflection, and hence neuroethics is born.

In all social milieu the suffix “neuro” is taking a stance to promote, sell, convince… One might be quietly eating a chocolate bar and on opening the candy wrapper find a picture that tries to illustrate the profound “scientific” sense of human love as nothing more than a collection of brain neurotransmitters: dopamine, oxytocin, and so on.

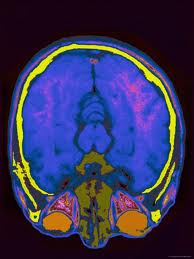

MRI images are almost part of our basic culture: words like PET (positron emission tomography) or functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) are already part of our memory. We have heard them on the radio and television; we read them on the Internet.

The first question that may arise is about the reason why they are so famous. Pictures of the human brain, x-rays, MRI results with little red and yellow dots are found today in any debate topic: from the medical sector to the psychological, the economical to the political, the philosophical to the theological, creating a real “neuromania.” We can already google (new term used by Google fans) all the terms that start with the suffix “neuro” that we want and we can almost be certain to find its existence and relating descriptions. Neuroeconomics, neuropolitics, neurophilosophy, neurotheology… are just some examples from this veritable gold mine. Everything seems to be explained by the greater or lesser activity of our brain.

A second question is related to the content, that is, to the information that these images withhold. What is it that they reveal? The results of neuroimaging are useful to study brains function and indicate the greater or lesser activity of zones of the brain in comparison to a control standard.

The objective of these very advanced techniques is to understand better how our brain works. This is true both in the medical world, for example, in the case of diagnosing brain diseases such as tumors, and also in the context of studies that endeavor to understand the neurophysiological bases for human activities such as memory, language, vision, and personality. One always needs to keep in mind the interpretation of these images, though. In fact, the interpretation of the results (in this case as in other cases in the context of the modern scientific method) is governed by the assumptions and theories developed by each laboratory—one might even say, each scientist. So we are faced with a potential diversity of interpretations for the very same empirical result.

The fascination of these scientific advances can in no way take the place of the necessary prudence which one must employ to discern and process the results.

The public remains captivated by the multitude of perspectives and real concrete applications of these technologies. For example, the so-called “brain trademarks or brain fingerprinting”, which measure brain waves and distinguish between true and false responses, have replaced the obsolete psychosomatic lie-detectors used in the courts. There are also brain electrodes that are being tested on patients with Parkinson’s or chronic depression, and so forth. Some scientists are working on the construction of microchips that take the place of brain memory areas damaged by Alzheimer’s, stroke, epilepsy, and other sicknesses.

These invaluable benefits to the quality of human life are confronted with numerous ethical questions that arise from the use of these discoveries for less noble purposes. We might consider the possibility of “mind control” that could be applied at a social level; or the real, already effective strategies that use neuroscience in order to understand and modulate purchasing decisions, the so-called neuromarketing.

In the middle of a fragmented and superficial culture such as the one we live in, we need a good dose of prudence, namely the correct reason one needs when taking actions and formulating conclusions, especially those that imply the existential and fundamental aspects of our lives. That is to say, it isn’t indifferent whether we believe that it is our brain and not us that acts, reasons, and makes judgments. These beliefs—because that is what they are, seeing that they are asserted without any basic foundation from a modern scientific context—have very deep repercussions on our actions, even the way we relate to others and ourselves.

At the center of neuro science, as in all other intellectual and human activities, there isn’t a brain, but a person. It is the human person, and not his brain, that thinks, plans, dreams, acts, loves, and cries. It is he who can inquire about his own brain, discover its workings, and bring to light, little by little, its mysteries.

science, as in all other intellectual and human activities, there isn’t a brain, but a person. It is the human person, and not his brain, that thinks, plans, dreams, acts, loves, and cries. It is he who can inquire about his own brain, discover its workings, and bring to light, little by little, its mysteries.

John Paul II summarizes it very well in his discourse to the members of the Pontifical Academy for the Sciences the 10 of November 2003: “Neuroscience and neurophysiology, through the study of chemical and biological processes in the brain, contribute greatly to an understanding of its workings. But the study of the human mind involves more than the observable data proper to the neurological sciences. Knowledge of the human person is not derived from the level of observation and scientific analysis alone but also from the interconnection between empirical study and reflective understanding. Scientists themselves perceive in the study of the human mind the mystery of a spiritual dimension which transcends cerebral physiology and appears to direct all our activities as free and autonomous beings, capable of responsibility and love, and marked with dignity.”

If the various realities of the human person are not distinguished while its complexity is acknowledged, everything becomes homogeneous, horizontal, simple, controllable, and subject to manipulation. The “soul” would become analogous to the “I,” and the “I” to the brain, and hence the technological mindset will prevail and reduce man to a materiality that does not even correspond to that of a brute animal. Hence the widespread mentality today that continues to consider “the problems and emotions of the interior life from a purely psychological point of view, even to the point of neurological reductionism.” (Caritas in Veritate, n. 76).

The human person is at the center of the multidisciplinary discussions about neuroethics, man in his unity and totality, with all his dimensions, with all his constituents: material, mental, and spiritual.

For this reason James Giordano of Oxford in 2005 proposed the term neurobioethics, hoping to stimulate common research from the contributions of neuroscience and the philosophical-anthropological vision which is centered on the human person.

In an environment of interdisciplinarity, neurobioethics tries to collect, select, evaluate, and interpret the data available to neuroscientists while highlighting the most salient ethical issues through a multidisciplinary approach and make evident the central role that the human person has because of his or her individuality, intrinsic value, and dignity, in any area of neuroscientific research (www.neurobioetica.it; www.neurobioethics.org).

Neurobioethics looks for points in common with other human disciplines to expand rationality itself and help to give a comprehensive response to the urgent ethical issues that are accumulating day by day.